By Toril Moi

Getting closer to life in an existentialism lecture reworked as a double seminar.

I applied for the Bacca Fellowship planning to teach a seminar on autofiction, focusing on recent writers such as Annie Ernaux, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Rachel Cusk, and Sheila Heti, who all, in different ways, try to get as close to life as possible. I had only taught this seminar once before, and I wanted to overhaul it. The Bacca Fellowship seemed the perfect opportunity to rethink the course.

But the meaning of life appears to be back in fashion. My other seminar, on existentialism, was oversubscribed within minutes. The waitlist grew so long that I canceled my course on autofiction and added a second section of existentialism. Both filled up. For the first time in my life, I was going to have to teach the same seminar back-to-back. I certainly needed Bacca help.

I had no idea what prompted the intense interest in existentialism. When I asked some undergraduates, they told me that they wanted to learn what makes life meaningful. Last year, they added, the course everyone was taking was one on happiness. For me, this was not entirely good news. For my course really doesn’t offer much uplift. On the contrary, the writers and thinkers who make up the existential tradition in literature and philosophy are a rather dour bunch. Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Ibsen, Hofmannsthal, Heidegger, Camus, and Beckett all rather relentlessly focus on the experience of meaninglessness. They come up against the limits of reason, wrestle with the death of God, and reject conventional notions of good and evil. In their fiction and theatre, they create characters who are either despicable or deeply depressed, or both. They worry that life may be absurd and declare that suicide is the only serious topic for philosophy. The few writers who do believe in action and meaning—Sartre, Beauvoir, Fanon—also discuss bad faith, oppression, and alienation in unsparing detail.

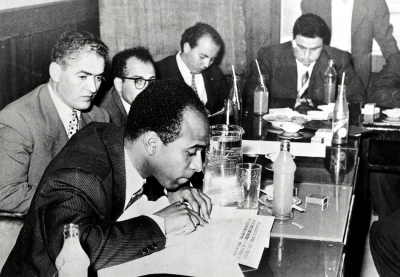

In the end, however, existentialism is not just about rejecting tradition. It is about lived experience: how to think about it, how to make sense of it, how to find the philosophy in our everyday experiences. And it can’t be all tragic. We ended term by watching Groundhog Day (1993), a romantic comedy packed with existential themes. Twentieth-century existentialists are also deeply interested in embodiment, in what it means to live in the world with a particular kind of body. We read Simone de Beauvoir, Frantz Fanon and Leslie Feinberg to get a better grasp of what it means to claim, as Beauvoir does, that the body is a situation. And, above all, existentialism is about freedom. It turns out that Duke students in 2023 are passionately interested in such things. The course was a joy to teach.

It was also hard work. I had taught existentialism many times before as a lecture course. Now I had to reorganize it as a seminar. In addition, I had taken on two Teaching Apprentices (TAPs) from the English department. TAPs aren’t expected to do all that much in a class. But they are supposed to be given various opportunities to develop as teachers. At the last minute I learned that I had also been given two TAs from the Literature Program. How could I figure out how to give them some meaningful work in a seminar? Of course, TAs can teach a little, and also help grade papers. But I am so old-fashioned that I still can’t imagine not reading all the student papers for myself as well. Otherwise, how would I get to know what they were getting out of the course?

I am no expert on pedagogy, so I naturally assumed that there had to be lots of new and imaginative ideas about activities TAs can do in a seminar. In fact, I thought that I was rather remiss in not knowing about them already. I turned to one of the teaching experts in the Bacca seminar, Duke’s Learning Innovation Consultant Seth Anderson, and asked him if he knew of something like a good overview of the various options. He told me he really didn’t. But, he added, he had called the Graduate School and asked them. They told him that they had never heard of anyone not knowing what to do with a TA. Apparently, I had stumbled across a problem that doesn’t exist.

After brainstorming with Seth, I came up with an idea of online writing groups to help the students begin their papers – two short ones and one longer one. This turned out to be a popular option for the students. It certainly helped them write better, and with greater freedom.

I enjoyed the Bacca Fellowship. I hugely appreciated our discussions as a group. It was a joy to get to know my fellow Fellows. The Bacca Fellowship offered a space of freedom and creativity in a busy academic schedule.

IMAGE CREDIT: “Frantz Fanon at a press conference during a writers' conference in Tunis, 1959,” Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:02_Frantz-Fanon-lors-dune-conf%C3%A9rence-de-presse-du-Congr%C3%A8s-des-%C3%A9crivains-%C3%A0-Tunis-1959.jpg#/media/File:02_Frantz-Fanon-lors-dune-conf%C3%A9rence-de-presse-du-Congr%C3%A8s-des-%C3%A9crivains-%C3%A0-Tunis-1959.jpg , Public domain

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Toril Moi