Opening up to “Now” in a Multimedia Composition Class

Improv games and long-form listening in a digital writing class.

As LAMP Intern in Innovative Pedagogy, I’ve had the privilege of observing and participating in the Bacca Fellows’ learning community for the last two years. Here’s one takeaway I can share from Bacca experimentation in my teaching this semester: it’s ok, in fact, it can be great, to move away from a content-competency model and to focus instead on creative activities and relational bonding in the classroom.

I’m teaching a digital literacy and multimedia composition workshop called “W275: Cyber Connections: Communicating in a Digital Age.” This is my second year at the cybernautic helm, a treat for this medievalist who loves digital media and writing pedagogy. I had thought that re-teaching this course meant I could put my pedagogy on end-of-dissertation autopilot, reusing my readings and lesson plans from the first run. The assignments certainly stayed the same: group-writing a rhetorical analysis of a digital media story in its cultural context, and building and workshopping individual portfolios of digital compositions like podcasts, infographics, and multimedia essays. But in terms of content and approach, the course’s second iteration necessitated a complete re-write, given the wildfire spread of tools like ChatGPT and DALL-E since I taught it only a year ago.

This revolution in the digital landscape has in turn changed my orientation as instructor. Instead of trying to perform authoritative expertise in the digital tools we discuss and use in class, all too soon outdated, replaced, or challenged by AI, I’ve been inviting students to join me in exploring the limits of our knowledge together, in shared moments of partial knowing in the classroom.

I tried building ignorance into the classroom by embracing it as a generative starting point for collective learning. I asked students to sign up to lead short creative exercises and tech-tool presentations in their own areas of expertise or curiosity at the start of each class in the first half of term. Through these presentations we all learned about software applications that were new to us—like the fantastical virtual workspace Lifeat.io, a digital flash-card study system called Anka, and Tome, an AI “pitch deck”-generating app. One student gave a demonstration of her preferred podcast production app, Anchor, which directly helped others who were still new to podcasting. As for the creative exercises that students led, I was astounded by their enthusiastic delivery and warm reception—at 8:30 in the morning, no less! At presenters’ prompting, we drafted parallel lives à la Matt Haig’s Midnight Library. We wrote sentences without the letters “a” or “e” to see how arbitrary constraints could unlock innovation. We played with creative process concepts like the “swipe file,” a start-up-savvy version of a vision board. All of these small presentations during the first half of the semester helped forge a classroom ethos of vulnerability and mutual encouragement, which seemed to deepen students’ experiences of trust and growth while workshopping their portfolio projects. 10/10 will do again in my future teaching!

Another way my class courted the line between known and unknown in a shared “now” was by practicing improv-based exercises I had seen modelled by Dr. Nan Mulleanneaux, who led several Bacca workshops this year. For example, I ran her “What I Love About That” exercise in my class: Going around the room, the group collaborates to build The Ultimate Party, layer by layer. Each person contributes an important fantastical element to a no-limits vision of the celebration, responding to the previous sharer’s contribution with the acknowledgment, “what I love about that is . . .” before adding their own imaginative element. This had gone fabulously in the Bacca Fellows faculty workshop on a Thursday afternoon in February. But first thing Monday morning in my W275 course, with only half the number of participants? In our basement media classroom, heater and projector adding a sleepy hum, this game did not appear to electrify the class. Later in the semester, though, the students told me that this had been one of their standout, memorable moments. Perhaps the success of a classroom experiment is not always immediately measurable, pedagogical note to self.

I appreciate that uncertain space between experiment and assessable outcome even more since adding another exploration of “now” to my teaching, this spring: long-form media reception. I mean a scenario in which everyone just sits there, collectively watching or listening to a full-length recording. As a socially nervous instructor, I have never before let a group media activity continue for longer than a Superbowl commercial (a great prompt for rhetorical analysis). Running a film or audio clip for longer than five minutes had seemed like a gateway to student disconnect. But as I have been learning this year, with Bacca workshops and conversations filling my sails, apparent engagement (in the sense of coming quickly to shareable words) may not be the most reliable measure for students’ deeper analytical work.

Maybe this is something all educators learn early on. It was a revelation to me, however: when you want students to do complex analytical, synthesizing, or creative work (i.e., high up on the Bloom taxonomy pyramid), you have to give them a lot of time and space. Even more important in these days of GPT-4: if you want to be sure that they actually take this time, and that it becomes part of your learning community’s shared narrative and ethos, then it may be worth doing it together in the classroom.

So, inspired by the generous amounts of time and space earmarked for quiet exploration in the Bacca workshops, I asked my own class to engage twice in spaces of shared silent watching and listening to recorded digital media. In a class on narrative transition in multimedia, for example, we watched a sixteen-minute rotoscope animated film about indigenous storytelling, Daniel Janke’s fabulous How People Got Fire (2008). That experience went well enough that I tried the practice again a few sessions later, in a lesson on data gathering and media consumers’ agency, this time asking students to doodle on blank paper while they listened to a forty-five-minute podcast interview with Shoshana Zuboff, the scholar who coined the term (and wrote the book on) “surveillance capitalism.”

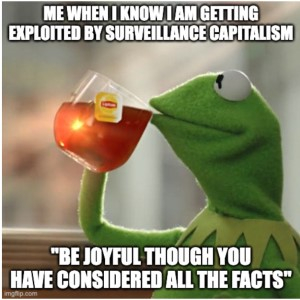

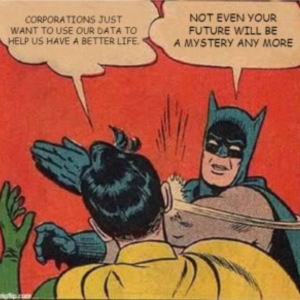

In both cases, when we flicked the lights back on and discussed these media selections afterwards, reception was muted. But students’ work in the assignments based on these long-form listening exercises impressed me. For homework after the Janke film, students captured screenshots of transitions they noticed and explained their selections to the whole class. I was so pleased to note the intricate effects they were able to articulate and the interpretive takeaways they synthesized. The Zuboff interview assignment went even better—I had asked them to pay substantial attention while listening (hence the doodling notetaking set-up), and then, for homework, to compose a meme combining elements of that interview with what they observed in an impassioned YouTube recording of the Wendell Berry poem, “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front” (1971). The resulting memes and explanations blew me away!

Whatever lack of engagement I had feared in these moments of long-form classroom media reception turned out to be beside the point. Through Dr. Mullenneaux’s improv workshops and Dr. Jennifer Ahern-Dodson’s work with the Bacca Fellows, I have gained a new confidence in creatively, patiently opening up to “now”—making room for collective learning and relationship building both in the classroom and out of it.

IMAGE CREDIT: Memes created by students in W275, Spring 2023, blending Shoshana Zuboff’s 2018 theory of surveillance capitalism with material from Wendell Berry’s 1971 poem “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front,” used with permission.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Joanna Murdoch